The Day The US Government Ordered the Overhaul of the Court.

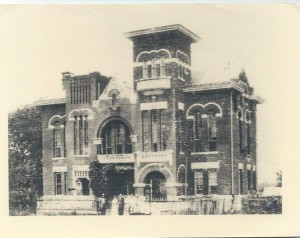

The sense of a contentious divide in the United States today worries me. But I found comfort while volunteering to preserve historical documents at the Charles Bacarisse Historical Document Room at the Harris County courthouse, (Houston, Texas). I came across this soul stirring entry in the minutes of the court, made announcing the end of the Civil War. The Judge who wrote these words, had just received the order from the US Government, mandating the overthrow and replacement of the sitting Confederate Judges, Supreme Court Justices and Jurors with those who swore an oath to the Union Government. The order also required that cases already filed in the court, be litigated according to Union laws.

The sense of a contentious divide in the United States today worries me. But I found comfort while volunteering to preserve historical documents at the Charles Bacarisse Historical Document Room at the Harris County courthouse, (Houston, Texas). I came across this soul stirring entry in the minutes of the court, made announcing the end of the Civil War. The Judge who wrote these words, had just received the order from the US Government, mandating the overthrow and replacement of the sitting Confederate Judges, Supreme Court Justices and Jurors with those who swore an oath to the Union Government. The order also required that cases already filed in the court, be litigated according to Union laws.

I could feel the anxiety of the court clerk as he wrote the words spoken by the Judge. I could imagine the agitation of the Confederate Judge who knew he was being unseated. Considering the tumultuous times, the sense of uncertainty of everyone in the courtroom who heard these words must have been overwhelming. Events show that in order to fulfill this order; the new Union Judge and the Confederate Judge spent weeks working together on the pending cases in order to preserve the primary principles of our country. See how our justice system flows in the best and the worst times of history.

Book K. Minutes of the 11th District Court of Harris County, Texas.

Thursday, June 1, 1865.

At our early day of the present term, it was announced that an order would be made to call for trial at the next term, all civil cases filed since January 1862. And but since the events in the history of the country have transpired which render it unnecessary to limit the call to any particular portion of the docket.

It is therefore ordered that at the next term of the court, the civil and criminal docket will be called for trial and disposition in full as in ordinary times. This order is entered now that all parties in interest have due notice.

Judge James A. Baker. Presiding Judge of the 11th District Court of Harris County Texas.

The importance of the dates noted in this order:

January 1862 Texas seceded from the United States on March 2, 1861 and became a Confederate State on March 23, 1861, which was during the first term of the court under the Confederacy and the new laws under the Confederate constitution. The Judge of the 11th Court, Judge James Addison Baker was an elected Judge. His great-great grandson, James Baker III would be US Secretary of State.

June 1, 1865 The Civil War had already ended on April 1865. But Confederate General E. Kirby Smith, didn’t surrender in Galveston, Texas until May. A Proclamation of Peace between the US and Texas wasn’t declared until August 20, 1866 over two months after the court order. Judge James A. Baker was the last district court judge in Harris County to serve under the Confederacy. The court’s docket had remained inactive from 1861 to the spring term of 1865 because of the war, so only five criminal cases and no civil ones were tried in Harris County. In Texas, the transition from the Confederacy to Reconstruction was anything but “ordinary.” Slavery was overturned , federal troops occupied Texas, and for the very first time the constitutional rights of former slaves were protected by the amended federal constitution.

What followed :

In August 1865, Judge James A. Baker is removed and replaced with Judge Colbert Coldwell by the Military Governor of Texas, Andrew Jackson Hamilton. The minutes show that all sitting Jurors were replaced with Union loyalists. All of the Supreme Court justices were removed from office as “impediments to Reconstruction” and replaced by order of the occupying Union government.

Judge Coldwell spent six days a week, pouring over a docket of disputes filed over the previous four years of the Civil War. Together he and Judge Baker bridged the legislative crevasse between the old and new constitutions. All this took place in the aftershock of a nation that had been at war with itself.

You can see these documents online at http://www.hcdistrictclerk.com/Common/HistoricalDocument/HistoricalDocuments.aspx

Sources: Texas State Library and Archive Commission https://www.tsl.texas.gov/ref/abouttx/secession/index.html) and Texas Historical Commission http://www.thc.texas.gov/public/upload/publications/tx-in-civil-war.pdf

The Confederacy’s Collapse and Houston’s Reconstruction By David Furlow http://www.hbaappellatelawyer.org/2014/03/the-confederacys-collapse-juneteenth.html