Court Interpreters are expected to know the correct word and phrase and usage for whatever we hear spoken by the questioner and by the respondent. So we study specialized terminology for specific industries. Even entry level interpreters learn the legalese used by the attorneys and Judge throughout each proceeding.

Court Interpreters are expected to know the correct word and phrase and usage for whatever we hear spoken by the questioner and by the respondent. So we study specialized terminology for specific industries. Even entry level interpreters learn the legalese used by the attorneys and Judge throughout each proceeding.

But beyond those fundamental terms, you could still be caught off guard by the unique words and phrases used by a witness who has had minimal formal education in their native language. They are communicating the way they are accustomed to and not necessarily in the same tone and word choices typically heard in the judicial setting. Another transformation in language happens when an expert takes the stand and you are interpreting full trial testimony for the Limited English Proficient (LEP) plaintiff or defendant. You will be swimming in very official, formal terminology and phrasing.

These distinctions in communication are called Register. Identifying it and duplicating it is another skill court interpreters must master. Register is a highly documented component of the field of linguistics. The professions we serve in the judiciary and law enforcement learn about register as part of Q&A procedures.

A professional court interpreter never passes judgment on the speaker by labeling their language as correct or incorrect. It is our job to learn all the different ways a person may choose to communicate so that we perform in accordance to our oath. Canon 1 of the Code of Ethics and Professional Responsibility [State of Texas regulations] states that we do not change the tone or register of the speaker. Learning about register is how you prepare yourself to recognize different registers and interpret accurately and completely while maintaining the register of the speaker.

There are five levels of register and each is spoken in identified settings by specific relationships of people.

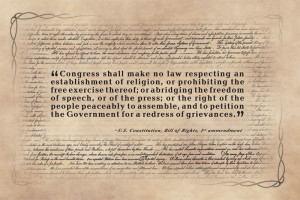

1. Static. This is a register of wording or phrasing that never changes. You do not state these in a lower register or simplify them. Examples would be a Pledge of Allegiance or the Miranda Rights.

2. Formal. This register is used when the wording carries weight and importance in its delivery. Formal register is used for speeches, sermons, rhetorical statements and questions, pronouncements made by judges, announcements.

3. Consultative Register. This language is formal but it is accepted comfortably as the societal standard for polite and professional language. It is used when strangers meet, communications between a superior and a subordinate, doctor and patient, lawyer and client, lawyer and judge, teacher and student and a counselor and client.

4. Casual Register. This is the informal language used by peers and friends. It frequently includes slang, vulgarities and colloquialisms. This is “group” language. Speakers must be a member to communicate in this register. People who use it are close friends, teammates, in chats, emails, and letters to friends.

5. Intimate Register This is the register of private communications. It is reserved for close family members or people who are intimate. This register is heard between husband and wife, intimate partners, between siblings, and parents and children.

In our line of work the most common levels are Static, Formal and Consultative. When your interpreting is flowing along in those three levels, if one of the speakers jumps into a Casual or Intimate register, our flow, especially is interrupted.

I can sense an oncoming change of register when a speaker is getting irritated. If they were speaking in a Formal register they will drop to Casual seemingly to show disdain for the questioning or the responsiveness. Or if they were feeling very familiar and unthreatened and then get irritated they will jump from Casual to Formal to display an imposed distance and ending the relaxed closeness they were exhibiting.

You will also see a body language shift that signals the change in register. The speakers’ posture and attentiveness display shifts when they change register. Often during in person interpretation settings, respondents will turn their bodies away from the questioner and face me directly. They will suddenly respond “yes or no Ma’am” directly to me, when the questioner is male and they had been responding with “Sir” up to that point. The standard rule for interpreting is to continue saying exactly what the speaker is saying so the gender shift will be reflected on the record. But this is a sign that the questioner has irritated the respondent. To see this happen, watch a few interrogation videos and you will see the shift and you will hear the change in register spoke. Actors are taught to display this with the dialogue they are given.

Skill Building Tools Expose yourself to examples of registers as expressed in your language pair. If Casual is what you hear most, immerse yourself in Formal. Develop that vocabulary. Stay attuned to the speaker and your interpreting will flow.

Exercise: Link the Register to the Speaking Event

Bailiff speaking to initial jury pool prior to voir dire.

Judge giving Jurors their Oath.

Testimony: Conversation during lunch hour between coworkers about upcoming layoffs.

Testimony: Police taking report at scene of vehicle accident.

Testimony: 911 call audio recording of assailant and victim in a domestic violence altercation.

I have worked with some of the best attorneys and Judges in the nation. And I love watching them work. Sometimes I am lucky enough when on subsequent cases, they reflect back on a trial or a proceeding and they explain to me what they were doing and why. These lessons can be applied to any interaction, conversation or discussion you have .

I have worked with some of the best attorneys and Judges in the nation. And I love watching them work. Sometimes I am lucky enough when on subsequent cases, they reflect back on a trial or a proceeding and they explain to me what they were doing and why. These lessons can be applied to any interaction, conversation or discussion you have .